Working through Robert Nystrom's Crafting Interpreters starting directly from clox.

Bytecode resembles machine code for a theoretical machine (the virtual machine). The emulator there adds overhead and makes these languages slower than natively compile languages (i.e. compiled to machine code) but they are a lot easier to write.

Note: If a piece of memory is already in the cache it can be accessed a lot faster. A lot of speed optimization is making sure that memory is found contiguously in the cache so that it can be retrieved.

Each instruction in bytecode has a one-byte operation code (opcode). The number defines the operation.

Bytecode is essentially a linear series of instructions that must be stored in an array; we don't know how long, so it is a dynamic array. These arrays are cache-friendly (what does this mean?) with constant-time element lookup. We can also append to them in constant time. In C we need to define both the capacity of the array and what number has been allocated already.

If there is still space in the array, we can directly add to it.

Otherwise the process is to:

- Make a new array with more capacity

- Copy to elements, store the new capacity

- Delete the old array

- Update the variable to point to the new aray

- Store the element in the new array and update the count

This is still O(1) but I don't quite understand why. There's some logic to grow the array by a factor of 2 in src/memory.h starting with 8 bytes. Memory allocationn is handled by a function called reallocate which can either allocate new blocks, free allocation, shrink an existing allocation, or grgow allocation depending on the oldSize and newSize parametes. A lot of the meat of this is done with the realloc funcntion (which is a generalization of the malloc function) from the std lib.

Details: realloc() can only grow the array if there is memory available after the block is free; if it's not, it grows a new block of memory somewhere else, copies over the contents, and deletes the old block. It's better to catch the case where this process fails than to let it return a null pointer. There is additional bookkeeping going on with the heap-allocated memory that allow realloc to clear the previous block, as all we're passing in is just a pointer to the memory address.

We also add some boilerplate to clear the memory associated with a chunk in freeChunk.

To help with the debugging, we define a "disassembler" which is the inverse of an assembler and will allow us to inspect machine code (basically).

We can store code in bytecode like this, but we need to have a statement to actually produce data (a constant). How should we represent these values? We're going to start by supporting only double precision floating point numbers. This is the Value type in value.h which is an abstraction above types in C so that we can switch it out later if we want.

We have a few options on how to store these. The first is right after the code stream next to the opcode, called immediate instructions because they're immediately right there. This doesn't work well for large or variable sized constants. In a native compiler, these are put into a seperate "constant data" region in the bin. The offset is basically stored so that it can be accessed. Each chunk here will keep a list of the values that appear as literals in the program, and just to keep things simple, we'll put all the data there. There are some additional complications with working with immediate instructions.

The constant pool needs an array of values and an address to load them in. We need a dynamic array for this. We implement these in the values.h and add methods to store these in the chunks. We need an opcode to actually deal with these constants (i.e. load them). The OP_CONSTANT actually nneeds two bytes, one with the opcode and the other with the address of the constant in the array.

Each opcode determines the number of bytes that is has and what they mean, so we need to have these in instruction format. When we write the chunk, we write the opcode for the constant and its address. This allows us to retrieve it in the debugger and to print it from value.h.

This is most of the basic information, amazingly. s The next thing we need is to be able to display the line number of runtime errors. We need to be able ot determine the line of the user's source program from its compiled from. We can use here a seperate array of line information. One of the nice things that simplifies our implementation is that this array will be the exact same size as our instruction set, so we don't need to keep track of more variables. This is very memory inefficient, but conceptually simple. We can print these out with the debugger pretty easily.

The entire AST is replaced by three arrays: bytes of code constant values, and line information.

Note:

- I have made some partial progress on the first challenge, stored in a feature branch here, but did not have a chance to finish it. I'm moving on to chapter 15 now.

A virtual machine here executes the instructions from the bytecode. In this implementation we use a single global VM. A different way of doing this would be to pass around a pointer to a VM through many different places, which may be more efficient for more complex languages.

We keep track of where the VM is in the bytecode using a pointer called ip or instruction pointer for legacy reasons. IP points to the instruction about to be executed, or the next instruction.

The run function does a lot of the meat of the computation with the language. It's a loop over all the bytecodes, using the IP as the index, with a switch for the different OP codes. That makes a lot of sense; when it sees a different OP code, it does something different. The reading is done through the READ_BYTE macro, by looking at the byte currently pointed at by IP and advancing the pointer. This is called "dispatching" or "decoding". This simplicity is a lot of the reason why it is so fast.

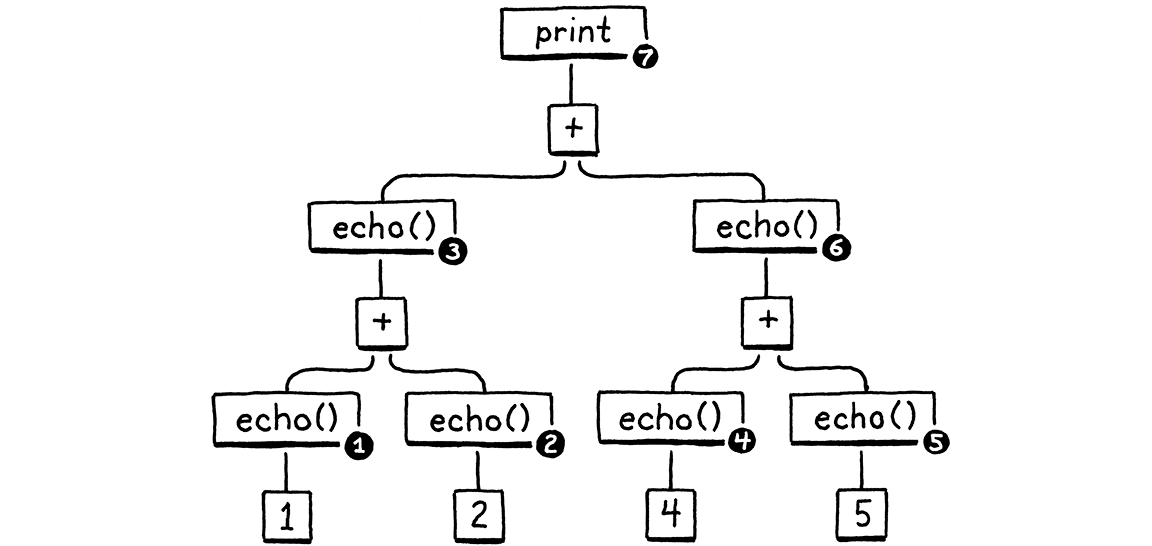

We also need a way to move values around. Like the instruction print 3-2, the 3 and 2 need to be stored and then the interpreter needs to know how to subtract htem.. In the java implementation, this tree is walked recursively to figure out all the values in the right order

Our run() function is not recursive in clox. It is linear, just a series of bytes. There's an interesting way to address this, which is basically tracking when the numbers are consumed and fill in those gaps with the new values.

The first number to appear is the last to be consumed. Last-in, first-out. That's a stack (not a heap). We push numbers onto the stack from the right; when they are consumed they pop off from the most right to the most left. When the instructions produce a value, it pushes it onto the stack. When it needs to consume these, it gets them by popping them off the stack.

The stack is basically a raw C array. The bottom is element 0 and we grow the stack on top of it. We use a direct pointer instead of an integer index because it's faster to dereference a pointer than calculate the offset with an integer. The stack_top refers to the place where the next pushed value will go (sort of like IP). There's a max to this stack, and if you go over it you get the classic "stack overflow".

This stack basically is how constants should be stored from above (where it wasn't very clear). The constant gets pushed onto the stack and then when asked to return it, it is returned.

To create a unary operator that negates a value, we can create a case that returns the negative of the last value on the stack. This is pushed back on top of the stack (index -1 then +1) so that it is available.

For binary operators, we use a macro BINARY_OP that takes in the C operator and uses it in a macro. A macro will just use this as text and expand it out anyway, which is kind of a crazy use of a macro. Macros are super low level and will accept basically anything... Including a function!

A binary operator takes two operands, so it pops twice. It performs some operation then pushes the result to the stack. We do this effectively backwards to take off the second one from the stack ebfore the first one.