The distraction-free text editor of musical programming languages.

Try it out!

Since I've been tinkering with music composition, mostly to understand it better, I thought it could help if I could construct music out of functions. A lot of musical passages walk up or down the scale in patterns of one or two scale degrees, which would be easier to write as a formula into which I could plug in values (thinking like a programmer). So I looked into musical programming languages, but...

- Many of them operate at too low of a level: sound synthesis, rather than plain piano keys. By analogy, if music were text, I'd want a text editor, not a graphical design suite.

- Even the ones that stick to a piano's 12 equal-tempered tones operate at the level of absolute pitch. Layering musical passages makes more sense (to me) in relative pitch.

- Many of these languages aren't intended for composition; they expect you to know which notes you want to write before you write them. (Can you believe that?)

- Very few allow for functional composition, and most that do are dialects of Lisp or Forth, which gets too far away from the musical mindset.

Doremi is a simple language for jotting down musical ideas and immediately hearing what they sound like, particularly as functions:

f(x) = do x

f(so) f(la) f(ti) f(la)

is the same as

do so do la do ti do la

The use of solfège, rather than absolute pitches, keeps me in a relative mindset, and duration is primarily expressed with the length of ASCII art dots, rather than numbers:

do.. fa.... la do la.... so.. fa.... re.. do....

Doremi is not on PyPI or conda-forge yet, so you'll have to install it from this repo. Beyond its built-in Python dependencies, it requires FluidSynth to synthesize sounds, and maybe someday Lilypond to generate images of music in standard notation. Both of these are only requirements if you use their respective functionality, though it's hard to imagine not wanting to synthesizing sounds. (Perhaps we could write MIDI files?)

# get fluidsynth from a standard distribution, such as apt or conda

apt install fluidsynth

conda install -c conda-forge fluidsynth

# note: lilypond is not used yet

apt install lilypond

git clone https://github.com/jpivarski/doremi.git

cd doremi

pip install . # gets Python dependencies (lark, regex, numpy) and installs doremiThe empty-template.ipynb consists of the following, which runs in Python:

import doremi

doremi.compose("""

do.. re.. mi..

""").play()Python is the host/implementation language; Doremi is inside the quoted string. The compose function can also take these arguments:

scale(e.g."major","D minor","E Mixolydian","WholeTone") with 1490 modes to choose from, thanks to allthescales.org. Alternatively, the scale can be constructed as a dict that maps note name (str) to pitch (floatfrequency orstrnote name)bpm(beats per minute), default is 120 BPM

The play method can take the above arguments (overriding scale and bpm) and also

emphasis_scalingto assign loudness to note emphasis (!)

A Composition object (created by compose) can

- report its

duration_in_seconds - return a N×2 (stereo) sound waveform array from

fluidsynth()(withdtypeasnp.int16ornp.float32); uses Nice-Steinway-Lite-v3.0.sf2 from soundfonts4u or your ownsoundfont play()the waveform in Jupyter (as shown above)show_notes()as ASCII text

(future: show() an SVG graph of notes in Jupyter and show notes in standard musical notation with lilypond).

A basic composition is a line of solfège names on a single line, in which each note is followed by dots to indicate duration. One dot (or no dots) is an eighth note, two dots is a quarter note, four dots is a half note, eight dots is a whole note, etc.

A line of music should look a bit like ASCII art, with the horizontal scale roughly proportional to time.

mi mi mi do......

Rests (no sound) are underscores with the same length-interpretation as dots.

mi mi mi ___ do......

The above rests for the length of 3 eighth notes; followed by a do for 6. Each of the mi notes is 1.

For our purposes, the solfège names of the 12 notes of an (equal-tempered) chromatic scale are

| name | do | ra | re | me | mi | fa | se | so | le | la | te | ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| half-steps | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| pronunciation | /doʊ/ | /ɹɑː/ | /ɹeɪ/ | /meɪ/ | /miː/ | /fɑː/ | /seɪ/ | /soʊ/ | /leɪ/ | /lɑː/ | /teɪ/ | /tiː/ |

| in major scale? | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

This is a "moveable do" system: the relative pitches of these notes are fixed, but the absolute pitch of "do" moves with the key signature of the scale (passed to compose or play in Python; see above). If you want to transpose a composition, just pass a different scale name as the second argument of compose.

If you provide a scale as a Python dict, rather than picking one from the database, you can name the notes whatever you like, such as

{"Sa": "c3", "Ri": "d3", "Ga": "e3", "Ma": "f3", "Pa": "g3", "Dha": "a3", "Ni": "b3"}or

{"স": "c3", "র": "d3", "গ": "e3", "ম": "f3", "প": "g3", "ধ": "a3", "ন": "b3"}or (for a just-tempered scale)

c3 = 130.82 # Hz

{

"do": c3,

"re": c3 * 9/8,

"mi": c3 * 5/4,

"fa": c3 * 4/3,

"so": c3 * 3/2,

"la": c3 * 5/3,

"ti": c3 * 15/8,

}(Note: at the moment, non-equal tempered notes can't be synthesized, so a just-tempered scale can't be played.)

If you change the names of the notes in a scale, you'd have to write

Ga Ga Ga Sa......

or

গ গ গ স......

All Unicode letters are recognized; note names can contain numbers, underscores, and the number sign (#) for perhaps-obvious reasons.

In addition, the scale degrees can be referenced directly as 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc. In a major scale, the following are equivalent:

mi mi mi do......

and

3rd 3rd 3rd 1st......

but if you set scale="minor", the second would become

me me me do......

Solfège is relative to the base key of the scale, but scale degrees also depend on the mode of the scale. (Therefore, they're good for exploring weird modes.)

Sequential notes have to be arranged on a single line without line breaks because multiple lines represent multiple voices or chords.

do''.... ti'.... do''........

fa' .... re'.... mi' ........

la .... so .... so ........

fa, .... so,.... do ........

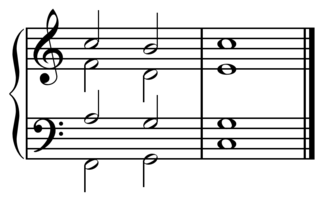

is

The single quotes (') and commas (,) following each note indicate octaves: in a C scale, do' is middle C (following the Helmholtz convention). Since the name of a note takes a variable number of characters, it can be helpful to line up the dots as much as possible. Rests (expressed as underscores) allow you to line up the notes.

do.... so.... me...... re.. do .. me.. re .. do.. ti,.. re.. so,....

____ ____ ______ __ do'.... so'.... me'...... re'.. do'....

With the single-line requirement for sequential notes, a long piece of music would quickly get out of hand. For that reason, paragraphs represent sequential phrases that follow each other. Paragraphs are separated by an empty line, as in Markdown or TeX. The following is equivalent to the example in the previous section:

do.... so.... me...... re..

____ ____ ______ __

do .. me.. re .. do.. ti,.. re.. so,....

do'.... so'.... me'...... re'.. do'....

Since the second line of the first paragraph has no notes, it can be simplified:

do.... so.... me...... re..

do .. me.. re .. do.. ti,.. re.. so,....

do'.... so'.... me'...... re'.. do'....

Not all phrases have to have the same number of voices. Generally, each paragraph would correspond to about a measure or two of standard musical notation. It can also be a convenient way to "reset" all the voices to align them in time without counting up durations by hand.

Basic durations are expressed as dots, with

- one dot (or no dots) equivalent to an eighth note

- two dots equivalent to a quarter note

- four dots equivalent to a half note

- eight dots equivalent to a whole note, etc.

To allow notes shorter than an eighth note, to construct tuplets, or to avoid clutter in the description of a slow passage, durations can also be assigned as numbers. The number is separated from the note using a colon (sideways dots) and it can be any fraction (like 1/4, not 0.25).

mi mi mi do:6

is the same as

mi mi mi do......

To modify the timing of a group of notes, enclose them in curly brackets ({ and }).

{mi mi mi}:2 do:4

This grouping is a general principle: any modification that applies to a single note applies to a group of notes in curly brackets. For example, octave marks (' and , described above).

{ {mi mi mi}:2 do:4 }'

(Plays one octave higher.)

The number after the colon specifies the total duration of the note or group. If, instead, you want to multiply the duration by a factor, use :* instead of :. The following are equivalent:

{do so do le do so do se} : 6

and

{do so do le do so do se} :* 6/8

The first ensures that the phrase takes the time of 6 dots (eighth notes) and the second scales the time by a factor of 6/8. They're equivalent because the phrase itself adds up to 8 dots, but both are provided to avoid having to manually count it.

Note that durations are fractions (like 6/8, not 0.75).

A note or phrase can be repeated by multiplying it (*) by an integer. As with durations, this can apply to a single note or a group in curly brackets.

{do so do le do so do se} * 2

or

{do so do le do so do se} * 2

do, * 16

The second example plays 16 low do, notes while playing the top sequence twice.

The pitch of a note or a group of notes can be tweaked in three ways:

- adding or subtracting half-steps:

+,++,+3,-1,-2,---, etc. - shifting up or down by scale degrees:

>,>>,>3,<1,<<,<<<, etc. - scaling the frequency of the sound:

% 3/2for a perfect fifth, etc.

The symbols that augment by half-steps are plus (+, increasing pitch) and minus (-, decreasing pitch), and the symbols that augment by scale degrees are greater than (>, increasing pitch) and less than (<, decreasing pitch). In both cases, the sign can either be repeated some number of times or appear only once followed by an integer.

Scaling by a frequency is different: it's always a percent sign (%) followed by a fraction (like 3/2, not 1.5). (Note: at the moment, non-equal tempered notes can't be synthesized, so frequency-scaled notes can't be played.)

Thus, the phrase

do so do le do so do se

could have equivalently been written as

do so do so+1 do so do so-1

but if it were written as

do so do so>1 do so do so<1

then it would only be equivalent if the scale were "chromatic". Scale degree augmentations are sensitive to the choice of scale; half-step augmentations are not.

Sometimes, we want to apply pitch augmentations to a group excluding some note, such as the root of the scale (do or 1st). The symbol to keep a note "at where it is" is the at-sign (@).

In the following, the do is not affected by the -2 and -4.

{@do do' ti la so....}

{@do do' ti la so....}-2

{@do do' ti la so....}-4

do re mi le so....

(At-signs are cumulative: if two augmentations are applied to the same note, through nested grouping, @@ would prevent all augmentation but @ would only prevent the inner-nested augmentation. Similarly for three at-signs, @@@, and so on.)

You may be wondering why we use at-signs at all when the above could have been written as

do {do' ti la so....}

do {do' ti la so....}-2

do {do' ti la so....}-4

do re mi le so....

The answer to that question gets at the core feature of this musical language...

The 12 solfège words (or alternatively, whatever you've defined in your scale) and 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc. are only the first words to be defined. New ones can be added through assignment with an equals sign (=):

cascade = @do do' ti la so....

finale = do re mi le so....

cascade cascade-2 cascade-4 finale

These assignments are definitions, which are not played as part of the piece unless explicitly referenced. The only line in the above that gets synthesized into sound is the

cascade cascade-2 cascade-4 finale

which inserts the cascade phrase as though it were a note, augmenting it each time. The finale is also a predefined phrase, though these phrases and individual notes can be mixed.

cascade cascade-2 cascade-4 do re mi le so....

Phrases can also be played concurrently.

cascade cascade-2 cascade-4 do re mi le so....

____ cascade cascade-2 cascade-4 do ra do..

Also, new symbols can incorporate concurrent voices, such as the chords in this progression:

I =

do

mi

so

V =

ti,

re

so

vi =

do

mi

la

IV =

do

fa

la

{I V vi IV}:16

is

(Perhaps these standard chord names should become built-in symbols.)

Technically, a user-defined symbol is a zero-argument function. Functions take arguments, which are notes, other predefined phrases, or groups of them. Function arguments are surrounded by parentheses, but they are not separated by commas because commas are used to lower octaves. Grouping (with curly brackets) may be necessary to separate arguments.

The following cascade is a function of the high note from which the descent starts. It expresses the same musical phrase as in the previous section in a different way.

cascade(start) = do start start-1 start-3 start-5....

cascade(do') cascade(te) cascade(le) do re mi le so....

Here's a phrase that needs to be defined in terms of two arguments: one descends while the other mostly ascends (except at the end).

f(x y) =

x<0 x<1 x<2 x<3 x<4 x<5 {y y>}:1 y<<

f(mi' fa) f(re' so) f(do' la) f(ti mi)

Formally, these are functions of only one data type: notes/groups of notes. The only way to get a function call wrong (in the sense that the program cannot proceed) is to pass the wrong number of arguments. Since these arguments are separated by spaces and spaces would ordinarily denote a sequence of notes, they'd have to be grouped if one argument is intended as a sequence.

f(x y) =

x<0 x<1 x<2 x<3 x<4 x<5 {y y>}:1 y<<

f({mi' mi'}:1 fa)

In the above, {mi' mi'}:1 (two quick notes) is the first argument, just as mi' previously had been, and fa is the second argument. Another way to perform this grouping is to define a new phrase:

f(x y) =

x<0 x<1 x<2 x<3 x<4 x<5 {y y>}:1 y<<

tmp = mi' mi'

f(tmp:1 fa)

but grouping with curly brackets means it can be expressed in place and doesn't need to be named.

(It's also worth noting that recursion is not allowed, since it could never terminate. In the hierarchy of programming language expressiveness, this is the lowest level: combinational logic. These programs always terminate/musical sequences always end in finite time.)

After pitch and duration, emphasis is a third dimension of a musical score. If we follow this line of reasoning to its logical conclusion, we'd also want to include timbre and the sounds of different kinds of instruments and we'd descend from this high-level abstraction into general composition. Therefore, Doremi has minimal syntax for emphasis: one or more exclamation points (!) before the note indicates a level of emphasis.

mi mi mi !do......

or

!mi mi mi !!do......

By default, this integer is interpreted as the "MIDI velocity," which is the loudness of a note, according to this Python function:

play(emphasis_scaling = lambda single, maximum: (single + 1) / (maximum + 1))That is, the notes with the maximum number of exclamation points are loudest; everything else scales proportionally with nothing at zero volume. It would be natural to scale this by a curve:

play(emphasis_scaling = lambda single, maximum: ((single + 1) / (maximum + 1))**(1/4))but this is getting beyond "high-level" and "distraction-free" composition that motivated this language, into the details of the sounds themselves.

As described above, notes and phrases (defined as functions or enclosed in curly brackets) can be displaced by an octave, stretched in time, repeated, augmented in pitch, prevented from being augmented, and can be emphasized. The general syntax is

emphasis? absolute? expression octave? augmentation? duration? repetition?

where

emphasisis an optional number of exclamation points (!)absoluteis an optional number of at-signs (@)expressionis a word, function call, or sequence in curly brackets ({and})octaveis a number of single quotes ('), commas (,), or one of these followed by a numberaugmentationis a number of plus (+) or minus (-) for half-steps, greater than (>) or less than (<) for scale degrees, or one of these followed by a number, or a percent sign (%) followed by a fraction (e.g.3/2, not1.5)durationis a number of dots (.), a colon (:) followed by fraction (to set an absolute duration), or a colon-times (:*) followed by a fraction (to multiply the duration by a factor)repetitionis multiplication (*) followed by an integer.

A single line of modified words represents one musical voice, a sequence of notes that follow each other in time. Multiple lines without an intervening line break represents multiple voices playing at the same time. Paragraphs separated by at least one line break represents separate phrases. If those phrases are not part of an assignment, they're played one after another.

Assignment has a form like name = or function(arg1 arg2) = (no commas between arguments) before a phrase, separated by at least one line break. There can be one line break after the equals sign (=) to line up the concurrent voices like ASCII art, but it's optional.

The only syntax element that has not been mentioned yet is the comment syntax: everything after a vertical bar (|) is ignored:

| This is a comment.

| It can go on for multiple lines.

mi mi mi do...... | It can go after a line of notes.

If a comment appears on a blank line separating two phrases, those phrases are still separated. For instance,

do re mi....

| comment

mi re do....

are two phrases played one after the other, not played at the same time. (The comment does not "join" them, as it would in TeX.)

That's everything. Have fun!