My solutions for 2023's Advent of Code.

Daily solutions' code is in the src/bin directory.

I recorded my solves on this YouTube playlist.

- Have fun & learn things

- Fast execution time (< 1 second for whole set of puzzles)

- Proper error propagation

- Actually learn how to deal with Result types and propagate errors up instead panicking

- Avoid crashes due to bad/unexpected inputs; use adversarial inputs if need be

- Avoiding external dependencies is a non-goal

- But only include well-known and defacto-standard libraries for specific purposes (e.g. regex, itertools, Rayon, anyhow)

You need to have Rust installed (see "rustup").

To run a single daily solution use:

cargo run --bin day_02_cube_conundrum < inputs/02/input.txt(You may type day_02tab to tab-complete the binary name 😉)

Or you can also pass it a sample file:

cargo run --bin day_02_cube_conundrum < inputs/02/sample.txtTo run all daily solutions with their input files run:

./run-allTo run all daily solutions in parallel and print their individual execution times:

PAR=1 TIMINGS=1 ./run-allAnd to check all sample files against their expected output and all input files against the answers on answers.txt run:

./check-allA surprisingly tricky first puzzle. Part 2 was required some actual thinking.

I learned about reading from stdin. In particular, using io::read_to_string(io::stdin()) to read the whole of it in one go.

One of those puzzles that involve more parsing than actual calculations, but it was fun actually :). I learned some patterns to work with Result types and properly propagate them up the call-chain, and some other tricks, for example:

- Using

try_collect()fromitertoolsinstead ofcollect::<Result<_, _>>()which is quite ugly. - Using

Option::ok_or("error message")for convertingOptions toResults and propagate them up with?. Super useful when parsing :) - And another useful function for parsing is

String::strip_prefix(); need to remember it for the future!

A grid puzzle with some tricky parsing problems, as the numbers on the grid span multiple cells and need to be consider as a single thing. I quite liked the use of usize::wrapping_add_signed() to be explicit about wrapping behavior and avoid having many back and forth as isize/usize conversions.

A simple and enjoyable Monday puzzle. Part 2 looked intimidating at first, but was relatively easy once given a little bit og thought :)

This one was a pretty straightforward part 1, but part 2 is too slow with the most naive approach of brute-forcing all the possible seed numbers. Luckily, Rust compiles to pretty efficient code, so even this brute-force solution was able to run in ~100 seconds on my machine :)

The Iterator::tuples() method from itertools was quite helpful in easily pairing numbers for part 2.

Update: after quite a bit of hacking, i managed to implement a non-brute-forcey solution based on interval math logic. This was a PITA; it took 2hs of hacking at vey questionable logic to to a working solution that yields the same answer. But it paid off: now the code runs in ~2ms instead of ~100s :D

Ignoring the pain, i think i've learned some important lessons regarding these kind of interval logic puzzles:

- Modeling abstract math operations like intersection and diff pays off really quickly. And the logic of these operations isn't even that involved!

- Using open-ended [start, end) ranges is better than start+length pairs. Way less fiddling with numbers and off-by-one errors.

A very simple puzzle that could be solved by brute force and still run fast enough. My input required to check ~50M numbers, just takes like ~5ms on my machine, so no need to find a better algorithm. Thanks again, Rust! :)

Nice domain-modeling puzzle. Part 2 was a neat twist to rethink some assumptions.

Learned the trick of using .zip(1..) instead of .enumerate() to enumerate things starting from 1.

Once again, i discover that implementing a custom Ord is not the most trivial thing. And learned a couple of lessons regarding ordering:

- Prefer using tuples of things as order keys, instead of custom

self.foo.cmp(&other.foo).then_with(|| ...)chains. Tuples or arrays already implement lexicographic order. - If possible, prefer deriving all ordering logic using

#[derive(Ord, PartialOrd)]. Enums can be trivially ordered, and structs get lexicographically ordered by their fields.

Trivial part 1 and quite tricky part 2. It didn't take me so long, but i stumbled upon the answer by chance really: it seemed that it was somewhere along the lines of counting loops through the node network and then doing some least common multiple of the times it took each ghost to reach an end. But i didn't expect to be just that! If you watch the recording for that day, you can see me getting both answers in ~1 hour and then spending another whole hour trying to figure out why the second answer was right.

Super nice and simple "mathematical" puzzle. A recursive solution worked wonderfully :chef-kiss:

Although, i learned that Rust's Result propagation does not provide an easy way of printing the stack trace by default. Not even the line location of the original error :(

There are some proposals to make error handling more ergonomic. See: rust-lang/rust#53487

Super challenging puzzle. Part 1 was relatively straightforward, but part 2... damn.

I couldn't come up with a clever and nice solution for part 2, so what i did was to "expand" the original grid threefold, converting each pipe tile into a 3x3 drawing of that pipe on the expanded grid. For example, the 4 tiles L-7| would get expanded to:

.#........#.

.#######..#.

.......#..#.

This allowed two pipes that seemed to be originally "touching", like the 7| above, to have some actual space between them in the expanded grid.

Then i flood-filled this expanded grid starting from the outside, so only the space inside the giant pipe loop does not get filled. And then it's easy to know which original tiles are inside the giant loop.

The "advantage" of this approach is that parts 1 and 2 are very independent. None of the pipe-walking logic from part 1 is relevant for part 2. And none of the part 2 flood-filling logic is relevant for part 1 either.

The disadvantage of course i that i couldn't reuse any common code between the two parts, and this felt like two completely unrelated puzzles.

After arriving to this eclectic solution, i went browsing on the AoC subreddit to see how other people have solved this, and i found out about a much more clever and elegant approach: scanning each row (or column) and counting how many piles belonging to the loop you go through. If you have passed an odd number of pipes, you're inside the loop, so any tile not belonging to the loop is inside it. It's much simpler, and of course much more tightly connected to part 1. Oh well! 🙃

Neat puzzle. Part 2 was a nice twist that invalidated my 2D-grid expansion solution for part 1, but it turned out to be be quite simple to implement with similar logic, but acting on the galaxies' positions instead of on the grid itself.

Iterator::tuple_combinations() from itertools was perfect for easily pairing up all galaxies :)

What a brutal part 2! Hardest puzzle so far.

Part 1 could be solved by brute-forcing all possible spring arrangements. But part 2 increased the input sizes fivefold, which, for an exponential

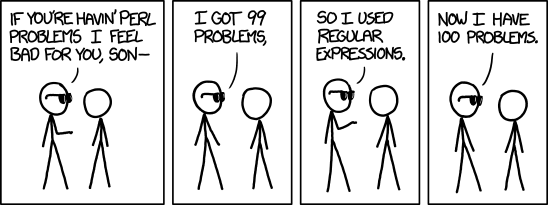

Two old tricks ended up doing wonders to cut this existential-crisis-inducing runtime: regular expressions, and caching.

Regular expressions were used to check whether a row of springs like ?###??..?? can match a given set of damaged spring group numbers like [3, 2]. Instead of implementing all the ad-hoc matching logic myself, the [3, 2] numbers get converted to the regex ^[.?]*[#?]{3}[.?]+[#?]{2}[.?]*$ that will only match spring rows that have or could have those groups of damaged springs, like .###.##.. or ?###??..??, but not ###..### or ?###?#..??. This way, the regex engine takes care of all the complicated matching logic and can tell us when a partially-decided arrangement is already invalid before resolving all the ?s into .s or #s. This cuts down branches of pattern-generation early and avoids trying out millions of arrangements that cannot possibly match the group numbers.

But even with the regex test cutting down the recursion branches greatly, the solution was still counting each single possible arrangement individually, which, for a final answer in the order of

The second trick was to cache and reuse results to avoid counting every arrangement individually. For example, for input line ?###???????? 3,2,1 (which is part of the example on the puzzle description), at some point we'll get to compute all arrangements for .###.##..???, which are 3. And then we'll get to a similar point but with a different position for the 2nd group: .###..##.???. Instead of recalculating all 3 arrangements again, we cache that result the first time and reuse it the second time.

This simple optimization cuts down the time to get to the answer from i don't know how much (i left it running for more than an hour) to half a second. Caches can be hard to get right, but they pay off.

Finally, using Rayon to iterate over all input lines in parallel brought down runtime ~540ms to ~130ms. Not bad at all considering this just mean changing a single .iter() call to .par_iter().

I'm incredibly grateful for high-quality crates like regex and rayon on the Rust ecosystem :)

Also i learned about Iterator::zip_longest() from itertools, which is incredibly useful for cases where you want to zip two sequences but also care about what happens when one is longer than the other. This was originally used to check if a row pattern matched some given group numbers, but ended up not being used on the final solution as it was replaced with the regex check mentioned above.

A total breather compared to the previous puzzle. Iterator::zip() came in very handy to pair up mirrored rows & columns and "discard" extra extra elements, as zip stops iteration when the first of the two iterators finishes.

Solid mid-difficulty puzzle. The rolling on the grid was implemented doing some very naive compare-and-swap logic, similar to Bubble Sort.

Part 2 required some cycle detection and modular math trick, but it wasn't that hard. I think this was similar a puzzle from a previous AoC.

Clocking at ~500ms, this one's the slowest solution thus far. It can probably be optimized a lot, either by using a more efficient rolling algorithm (which is very similar to sorting). Or by using a more machine-friendly model, like modeling rows and cols as single numbers and then doing the "rolling" as bit shifting a bitmask of round rocks and &ing with a bitmask of square rocks to detect collisions. Or even by doing parallel computation while rolling the rocks.

Incredibly simple part 1, and rather straightforward part 2, despite the long puzzle description.

Quite fun grid puzzle. I was expecting a challenging part 2, but nope, it was a pretty straightforward reuse of part 1 logic. It felt nice to chain 4 Iterator::chain() calls to iterate over all possible starting positions and directions on the grid.

A very original pathfinding puzzle. I ended up using the Dijkstra's algorithm from the pathfinding crate instead of implementing my own (i.e. copying it from one of my previous Rust AoC projects).

It was nice to model the "cannot go in a straight line for more than N blocks" rule into the successors function. And it was also quite satisfying to extract a common function to solve both part 1 & 2 with just two different parameter numbers.

Part 1 could be solved using our old friend: flood filling. But then part 2 required to basically do the same area calculation, but for a giant "lagoon". So instead, some more sophisticated algebra was needed. "Thankfully" my friend @riffraff had semi-spoiled this daily puzzle and mentioned he used the Shoelace formula on it. So i had some idea of what to look for.

This formula for a polygon area worked wonderfully, and was a breeze to implement thanks to Iterator::tuple_windows from itertools. The tricky pipe loop area for day 10 could have also been calculated with the Shoelace formula and some careful handling of pipe bends, instead of the brutish approach i used, of "inflating" the grid ninefold to then flood-fill it.

This day i also learned about Iterator::collect_tuple() from itertools, which can be used on parsing code to extract a known number of elements from an iterator into a tuple, instead of having to either do it.next() a bunch of times or collecting the iterator into a Vec and then pattern-matching the Vec into a slice pattern by making use of vec[..].try_into().

A very original puzzle. Part 1 was more about parsing and modeling the data we're working with, but nothing algorithmically challenging. And part 2 was the complete opposite.

I felt very satisfied of coming up with a working non-sucky solution for part 2 in one sitting. Although i'm sure a more mathematically-oriented person could have approached this in a much more straightforward way. I was completely lost for quite a bit hehe.

This puzzle was extremely... puzzling! Part 1 was easy enough to implement; no clever tricks. But part 2 was one of those hard puzzles that requires to understand the particular shape of the input, find patterns in it, and assume many things to find the solution. Or at least that's how i solved it. My implementation would not generalize to other inputs. See giant "Note" comment on the code.

Another 2D grid puzzle. For part 1, i could've implemented some custom BFS-like algorithm to find the reachable tiles, but i went for the lazy solution and reused the Dijkstra's algorithm from the pathfinding crate and counted only the tiles with the same parity as the required number of steps.

Part 2 was hard, and required some out of the box thinking. Once the connection between the astronomically large number of steps and the map size was noticed, and also the particular distribution of the walls in the map, it was a matter of thinking how to extrapolate the solution of small multiples of map sizes to the required size. Another one of these very-input-dependant solutions. Again, check the code comments for more clarification.

First 3D grid puzzle of AoC 2023! Fortunately, this wasn't as hard as the previous puzzles. Part 2 was an incremental complication over part 1, which actually allowed part 1 to be implemented in terms of the part 2 solution. Even though i was quite unfocused while doing it, it was a satisfying puzzles to solve :)

A graph traversal puzzle disguised as a 2D grid puzzle. Sneaky!

The logic for this one was not too complicated, but part 2 was computationally challenging, as the graph for which we need to find the longest gets more interconnected, and thus the number of possible paths increases quite enormously.

For part 1, a very dumb solution using a k-shortest paths algorithm from the pathfinding package was enough: just find all the paths from start to end keep the longest. But part 2 required something less barbaric.

The most complicated part of the code ended up being converting the initial grid into a weighted graph. After that, a DFS-like algorithm to traverse all paths on the graph and keep the longest was enough.

I found a very nice optimization when i realized that when traversing the graph nodes, instead of keeping a Vec of all previous nodes —which required a new allocation and copy every time we take a new path on the graph— we could just mark those visited nodes on a bitmask integer. This vastly cut down the runtime of the solution: from ~7.5s to ~300ms :)

A relatively simple part 1, though the algebraic part of my brain seems to have collected too much dust through the years, so this 2D intersection calculation didn't come to mind as readily as i would've liked.

Part 2 was on an entire other level of algebra. I had to think about it for the most part of a day, and ended solving it using Python on a notebook, due to a lack of symbolic algebra packages in Rust — and a lack of will on my part to think of another solution. But, even though i think i would have no chance of solving this system of equations with pen and paper, i'm glad of having come up with a working solution that makes some sense to me.

As a sidenote: i was very much disappointed by the lack of good online solvers for this kind of algebraic problems. Wolfram Alpha seems to be the most powerful and accessible tool, but it is arbitrarily caped, and of course a giant black box.

At the same time, i was blown away with the power and usability of sympy and Python (Jupyter) notebooks. Python's local environment setup is another story; one of sadness and pain. But maybe it is precisely because of how painful it is to properly set up a local Python environment that tools like Jupyter and Google Colab exist.

I wish a symbolic math package like sympy existed for Rust. Being a low-level language that can easily be interfaced with, a package like this could provide a common backend for multiple front-ends on different languages.

A graph-theory-heavy puzzle. Ended up implementing the Stoer–Wagner algorithm, which i initially copied from an existing C++ implementation but ended up modifying quite a lot to be more Rusty and also better fit puzzle requirements.

A pretty challenging puzzle to end this year's Advent of Code. But TBF i've felt nearly all puzzles from day 18 onwards have been pretty difficult, so this one was no surprise.