- 0.0 Setup

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Data

- 3.0 Types of Learning

- 4.0 Fundamentals

- 5.0 Optimization

- 6.0 Final Words

========================================================================

This guide was written in Python 3.6.

Machine Learning is the field where statistics and computer science overlap for prediction insights on data. What do we mean by prediction? Given a dataset, we generate an algorithm to learn what features or attributes are indicators of a certain label or prediction. These attributes or features can be anything that describes a data point, whether that's height, frequency, class, etc.

This algorithm is chosen based on the original dataset, which you can think of as prior or historical data. When we refer to machine learning algorithms, we're referring to a function that best maps a data point's features to its label. A large part of the machine learning is spent improving this function as much as possible.

You've likely heard of hypotheses in the context of science before; typically, it's an educated guess on what and outcome will be. In the context of machine learning, a hypothesis is the function we believe is similar to the true function of learning - the target function that we want to model and use as our machine learning algorithm.

In this course, we'll review different machine learning algorithms, from decision trees to support vector machines. Each is different in its methodology and results. A critical part of the process of choosing the best algorithm is considering the assumptions you can make about the particular dataset you're working with. These assumptions can include the linearity or lack of linearity, the distribution of the dataset, and much more.

In this course and future courses, you'll see lots of notation. I've collected a list of all the general notation you'll see:

a: scalar

a: vector

A: matrix

ai: the ith entry of a

aij: the entry (i,j) of A

a(n): the nth vector a in a dataset

A(n): the nth matrix A in a dataset

H: Hypothesis Space, the set of all possible hypotheses

As a data scientist, knowing the different forms data takes is highly important. When working on a prediction problem, the collection of data you're working with is called a dataset.

Generally speaking, there are two forms of data: unlabeled and labeled. Labeled data refers to data that has inputs and attached, known outputs. Unlabeled means all you have is inputs. They're denoted as follows:

-

Labeled Dataset: X = {x(n) ∈ Rd}Nn=1, Y = {yn ∈ R}Nn=1

-

Unlabed Dataset: X = {x(n) ∈ Rd}Nn=1

Here, X denotes a feature set containing N samples. Each of these samples is a d-dimension vector, x(n). Each of these dimensions is an attribute, feature, variable, or element. Meanwhile, Y is the label set.

When it comes time to train your classifier or model, you're going to need to split your data into testing and training data.

Typically, the majority of your data will go towards your training data, while only 10-25% of your data will go towards testing.

It's important to note there is no overlap between the two. Should you have overlap or use all your training data for testing, your accuracy results will be wrong. Any classifier that's tested on the data it's training is obviously going to do very well since it will have observed those results before, so the accuracy will be high, but wrongly so.

Furthermore, both of these sets of data must originate from the same source. If they don't, we can't expect that a model built for one will work for the other. We handle this by requiring the training and testing data to be identically and independently distributed (iid). This means that the testing data show the same distribution as the training data, but again, must not overlap.

Together these two aspects of the data are known as IID assumption.

The concept of overfitting refers to creating a model that doesn't generaliz e to your model. In other words, if your model overfits your data, that means it's learned your data too much - it's essentially memorized it.

This might not seem like it would be a problem at first, but a model that's just "memorized" your data is one that's going to perform poorly on new, unobserved data.

Underfitting, on the other hand, is when your model is too generalized to your data. This model will also perform poorly on new unobserved data. This usually means we should increase the number of considered features, which will expand the hypothesis space.

What's open data, you ask? Simple, it's data that's freely for anyone to use! Some examples include things you might have already heard of, like APIs, online zip files, or by scraping data!

You might be wondering where this data comes from - well, it can come from a variety of sources, but some common ones include large tech companies like Facebook, Google, Instagram. Others include large institutions, like the US government! Otherwise, you can find tons of data from all sorts of organizations and individuals.

Generally speaking, Machine Learning can be split into three types of learning: supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning.

This algorithm consists of a target / outcome variable (or dependent variable) which is to be predicted from a given set of predictors (independent variables). Using these set of variables, we generate a function that map inputs to desired outputs. The training process continues until the model achieves a desired level of accuracy on the training data. Examples of Supervised Learning: Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, etc.

All supervised learning algorithms in the Python module scikit-learn hace a fit(X, y) method to fit the model and a predict(X) method that, given unlabeled observations X, returns predicts the corresponding labels y.

In this algorithm, we do not have any target or outcome variable to predict / estimate. We can derive structure from data where we don't necessarily know the effect of the variables. Examples of Unsupervised Learning: Clustering, Apriori algorithm, K-means.

Using this algorithm, the machine is trained to make specific decisions. It works this way: the machine is exposed to an environment where it trains itself continually using trial and error. This machine learns from past experience and tries to capture the best possible knowledge to make accurate business decisions. Example of Reinforcement Learning: Markov Decision Process.

Though Machine Learning is considered the overarching field of prediction analysis, it's important to know the distinction between its different subfields.

Natural Language Processing, or NLP, is an area of machine learning that focuses on developing techniques to produce machine-driven analyses of textual data.

Computer Vision is an area of machine learning and artificial intelligence that focuses on the analysis of data involving images.

Deep Learning is a branch of machine learning that involves pattern recognition on unlabeled or unstructured data. It uses a model of computing inspired by the structure of the brain, which we call this model a neural network.

The variables we use as inputs to our machine learning algorithms are commonly called inputs, but they are also frequently called predictors or features. Inputs/predictors are independent variables and in a simple 2D space, you can think of an input as x-axis variable.

The variable that we’re trying to predict is commonly called a target variable, but they are also called output variables or response variables. You can think of the target as the dependent variable; visually, in a 2-dimensional graph, the target variable is the variable on the y-axis.

Another name for outputs or targets is labels. In this section we discuss the different types of labels a dataset can encompass.

- Single column with binary values -- usually a classification problem where a sample belongs to one class only and there are only two classes.

- Single column with real values -- usually a regression problem with a prediction of only one value.

- Multiple columns with binary values -- also usually a classification problem, where a sample belongs to one class, but there are more than two classes.

- Multiple columns with real values -- also usually a regression problem with a prediction of multiple values.

- Multilabel - also a classification problem, but a sample can belong to several classes.

When you’re doing machine learning, specifically supervised learning, you’re using computational techniques to reverse engineer the underlying function your data.

With that said, we'll go through what this process generally looks like. In the exercise, I intentionally keep the underlying function hidden from you because we never know the underlying function in practice. Once again, machine learning provides us with a set of statistical tools for estimate f(x).

This needs new code

Understanding how different sources of error lead to bias and variance helps us improve the data fitting process resulting in more accurate models.

Error due to bias is the difference between the expected (or average) prediction of our model and the actual value we're trying to predict.

Error due to variance is taken as the variability of a model prediction for a given data point. In other words, the variance is how much the predictions for a given point vary between different realizations of the model.

The bias–variance tradeoff is the problem of simultaneously minimizing two sources of error that prevent supervised learning algorithms from generalizing beyond their training set.

In the simplest case, optimization consists of maximizing or minimizing a function by systematically choosing input values from within an allowed set and computing the value of the function.

The job of the loss function is to tell us how inaccurate a machine learning system's prediction is in comparison to the truth. It's denoted with ℓ(y, ŷ), where y is the true value and ŷ is a the machine learning system's prediction.

The loss function specifics depends on the type of machine learning algorithm. In Regression, it's (y - ŷ)2, known as the squared loss. Note that the loss function is something that you must decide on based on the goals of learning.

Since the loss function gives us a sense of the error in a machine learning system, the goal is to minimize this function. Since we don't know what the distribution does, we have to calculte the loss function for each data point in the training set, so it becomes:

In other words, our training error is simply our average error over the training data. Again, as we stated earlier, we can minimize this to 0 by memorizing the data, but we still want it to generalize well so we have to keep this in mind when minimizing the loss function.

Boosting is a machine learning meta-algorithm that iteratively builds an ensemble of weak learners to generate a strong overall model.

A weak learner is any machine learning algorithm that has an accuracy slightly better than random guessing. For example, in binary classification, approximately 50% of the samples belong to each class, so a weak learner would be any algorithm that slightly improves this score – so 51% or more.

These weak learners are usually fairly simple because using complex models usually leads to overfitting. The total number of weak learners also needs to be controlled because having too few will cause underfitting and have too many can also cause overfitting.

The overall model built by Boosting is a weighted sum of all of the weak learners. The weights and training given to each ensures that the overall model yields a pretty high accuracy.

Many ensemble methods train their components in parallel because the training of each those weak learners is independent of the training of the others, but this isn't the case with Boosting.

At each step, Boosting tries to evaluate the shortcomings of the overall model built, and then generates a weak learner to battle these shortcomings. This weak learner is then added to the total model. Therefore, the training must necessarily proceed in a serial/iterative manner.

Each of the iterations is basically trying to improve the current model by introducing another learner into the ensemble. Having this kind of ensemble reduces the bias and the variance.

Because boosting involves performing so many iterations and generating a new model at each, a lot of computations, time, and space are utilized.

Boosting is also incredibly sensitive to noisy data. Because boosting tries to improve the output for data points that haven't been predicted well. If the dataset has misclassified or outlier points, then the boosting algorithm will try to fit the weak learners to these noisy samples, leading to overfitting.

Occam's Razor states that any phenomenon should make as few assumptions as possible. Said again, given a set of possible solutions, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected. The problem here is that Machine Learning often puts accuracy and simplicity in conflict.

What we've covered here is a very small glimpse of machine learning. Applying these concepts in actual machine learning algorithms such as random forests, regression, classification, is the harder but doable part.

Stanford Coursera

Math ∩ Programming

========================================================================

This guide was written in Python 3.6.

If you haven't already, please download Python and Pip.

Let's install the modules we'll need for this tutorial. Open up your terminal and enter the following commands to install the needed python modules:

pip3 install scikit-learn==0.18.1

pip3 install nltk==3.2.4

In this tutorial set, we'll review the Naive Bayes Algorithm used in the field of machine learning. Naive Bayes works on Bayes Theorem of probability to predict the class of a given data point, and is extremely fast compared to other classification algorithms.

Because it works with an assumption of independence among predictors, the Naive Bayes model is easy to build and particularly useful for large datasets. Along with its simplicity, Naive Bayes is known to outperform even some of the most sophisticated classification methods.

This tutorial assumes you have prior programming experience in Python and probablility. While I will overview some of the priciples in probability, this tutorial is not intended to teach you these fundamental concepts. If you need some background on this material, please see my tutorial here.

Recall Bayes Theorem, which provides a way of calculating the posterior probability:

Before we go into more specifics of the Naive Bayes Algorithm, we'll go through an example of classification to determine whether a sports team will play or not based on the weather.

To start, we'll load in the data, which you can find here.

import pandas as pd

f1 = pd.read_csv("./data/weather.csv")Before we go any further, let's take a look at the dataset we're working with. It consists of 2 columns (excluding the indices), weather and play. The weather column consists of one of three possible weather categories: sunny, overcast, and rainy. The play column is a binary value of yes or no, and indicates whether or not the sports team played that day.

f1.head(3).dataframe thead th {

text-align: left;

}

.dataframe tbody tr th {

vertical-align: top;

}

| Weather | Play | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Sunny | No |

| 1 | Overcast | Yes |

| 2 | Rainy | Yes |

If you recall from probability theory, frequencies are an important part of eventually calculating the probability of a given class. In this section of the tutorial, we'll first convert the dataset into different frequency tables, using the groupby() function. First, we retrieve the frequences of each combination of weather and play columns:

df = f1.groupby(['Weather','Play']).size()

print(df)Weather Play

Overcast Yes 4

Rainy No 3

Yes 2

Sunny No 2

Yes 3

dtype: int64

It will also come in handy to split the frequencies by weather and yes/no. Let's start with the three weather frequencies:

df2 = f1.groupby('Weather').count()

print(df2) Play

Weather

Overcast 4

Rainy 5

Sunny 5

And now for the frequencies of yes and no:

df1 = f1.groupby('Play').count()

print(df1) Weather

Play

No 5

Yes 9

The frequencies of each class are important in calculating the likelihood, or the probably that a certain class will occur. Using the frequency tables we just created, we'll find the likelihoods of each weather condition and yes/no. We'll accomplish this by adding a new column that takes the frequency column and divides it by the total data occurances:

df1['Likelihood'] = df1['Weather']/len(f1)

df2['Likelihood'] = df2['Play']/len(f1)

print(df1)

print(df2) Weather Likelihood

Play

No 5 0.357143

Yes 9 0.642857

Play Likelihood

Weather

Overcast 4 0.285714

Rainy 5 0.357143

Sunny 5 0.357143

Now, we're able to use the Naive Bayesian equation to calculate the posterior probability for each class. The highest posterior probability is the outcome of prediction.

Now, let's get back to our question: Will the team play if the weather is sunny?

From this question, we can construct Bayes Theorem. Because the know factor is that it is sunny, the

Since we already created some likelihood tables, we can just index P(Sunny) and P(Yes) off the tables:

ps = df2['Likelihood']['Sunny']

py = df1['Likelihood']['Yes']That leaves us with df, we see that the total number of yes days under sunny is 3. We take this number and divide it by the total number of yes days, which we can get from df:

psy = df['Sunny']['Yes']/df1['Weather']['Yes']And finally, we can just plug these variables into bayes theorem:

p = (psy*py)/ps

print(p)0.6

This tells us that there's a 60% likelihood of the team playing if it's sunny. Because this is a binary classification of yes or no, a value greater than 50% indicates a team will play.

Every classifier has pros and cons, whether that be in terms of computational power, accuracy, etc. In this section, we'll review the pros and cons of Naive Bayes.

Naive Bayes is incredibly easy and fast in predicting the class of test data. It also performs well in multi-class prediction.

When the assumption of independence is true, the Naive Bayes classifier performs better thanother models like logistic regression. It does this, and with less need of a lot of data.

Naive Bayes also performs well with categorical input variables compared to numerical variable(s), which is why we're able to use it for text classification. For numerical variables, normal distribution must be assumed.

If a categorical variable has a category not observed in the training data set, then model will assign a 0 probability and will be unable to make a prediction. This is referred to as “Zero Frequency”. To solve this, we can use the smoothing technique, such as Laplace estimation.

Another limitation of Naive Bayes is the assumption of independent predictors. In real life, it is almost impossible that we get a set of predictors which are completely independent.

With scikit-learn, we can implement Naive Bayes models in Python. There are three types of Naive Bayes models, all of which we'll review in the following sections.

The Gaussian Naive Bayes Model is used in classification and assumes that features will follow a normal distribution.

We begin an example by importing the needed modules:

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB

import numpy as npAs always, we need predictor and target variables, so we assign those:

x = np.array([[-3,7],[1,5], [1,2], [-2,0], [2,3], [-4,0], [-1,1], [1,1], [-2,2], [2,7], [-4,1], [-2,7]])

y = np.array([3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 4])Now we can initialize the Gaussian Classifier:

model = GaussianNB()Now we can train the model using the training sets:

model.fit(x, y)Now let's try out an example:

predicted = model.predict([[1,2],[3,4]])We get:

([3,4])

MultinomialNB implements the multinomial Naive Bayes algorithm and is one of the two classic Naive Bayes variants used in text classification. This classifier is suitable for classification with discrete features (such as word counts for text classification).

The multinomial distribution normally requires integer feature counts. However, in practice, fractional counts may also work.

First, we need some data, so we import numpy and

import numpy as np

x = np.random.randint(5, size=(6, 100))

y = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6])Now let's build the Multinomial Naive Bayes model:

from sklearn.naive_bayes import MultinomialNB

clf = MultinomialNB()

clf.fit(x, y)Let's try an example:

print(clf.predict(x[2:3]))And we get:

[3]

Like MultinomialNB, this classifier is suitable for discrete data. BernoulliNB implements the Naive Bayes training and classification algorithms for data that is distributed according to multivariate Bernoulli distributions, meaning there may be multiple features but each one is assumed to be a binary value.

The decision rule for Bernoulli Naive Bayes is based on

import numpy as np

x = np.random.randint(2, size=(6, 100))

y = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5])from sklearn.naive_bayes import BernoulliNB

clf = BernoulliNB()

clf.fit(x, y)

print(clf.predict(x[2:3]))And we get:

[3]

If continuous features don't have a normal distribution (recall the assumption of normal distribution), you can use different methods to convert it to a normal distribution.

As we mentioned before, if the test data set has a zero frequency issue, you can apply smoothing techniques “Laplace Correction” to predict the class.

As usual, you can remove correlated features since the correlated features would be voted twice in the model and it can lead to over inflating importance.

So you might be asking, what exactly is "sentiment analysis"?

Well, sentiment analysis involves building a system to collect and determine the emotional tone behind words. This is important because it allows you to gain an understanding of the attitudes, opinions and emotions of the people in your data.

At a high level, sentiment analysis involves Natural language processing and artificial intelligence by taking the actual text element, transforming it into a format that a machine can read, and using statistics to determine the actual sentiment.

To accomplish sentiment analysis computationally, we have to use techniques that will allow us to learn from data that's already been labeled.

So what's the first step? Formatting the data so that we can actually apply NLP techniques.

import nltk

def format_sentence(sent):

return({word: True for word in nltk.word_tokenize(sent)})Here, format_sentence changes a piece of text, in this case a tweet, into a dictionary of words mapped to True booleans. Though not obvious from this function alone, this will eventually allow us to train our prediction model by splitting the text into its tokens, i.e. tokenizing the text.

{'!': True, 'animals': True, 'are': True, 'the': True, 'ever': True, 'Dogs': True, 'best': True}

You'll learn about why this format is important is section 3.2.

Using the data on the github repo, we'll actually format the positively and negatively labeled data.

pos = []

with open("./pos_tweets.txt") as f:

for i in f:

pos.append([format_sentence(i), 'pos'])neg = []

with open("./neg_tweets.txt") as f:

for i in f:

neg.append([format_sentence(i), 'neg'])Next, we'll split the labeled data we have into two pieces, one that can "train" data and the other to give us insight on how well our model is performing. The training data will inform our model on which features are most important.

training = pos[:int((.9)*len(pos))] + neg[:int((.9)*len(neg))]We won't use the test data until the very end of this section, but nevertheless, we save the last 10% of the data to check the accuracy of our model.

test = pos[int((.1)*len(pos)):] + neg[int((.1)*len(neg)):]from nltk.classify import NaiveBayesClassifier

classifier = NaiveBayesClassifier.train(training)All NLTK classifiers work with feature structures, which can be simple dictionaries mapping a feature name to a feature value. In this example, we’ve used a simple bag of words model where every word is a feature name with a value of True. This is an implementation of the Bernoulli Naive Bayes Model.

To see which features informed our model the most, we can run this line of code:

classifier.show_most_informative_features()Most Informative Features

no = True neg : pos = 20.6 : 1.0

awesome = True pos : neg = 18.7 : 1.0

headache = True neg : pos = 18.0 : 1.0

beautiful = True pos : neg = 14.2 : 1.0

love = True pos : neg = 14.2 : 1.0

Hi = True pos : neg = 12.7 : 1.0

glad = True pos : neg = 9.7 : 1.0

Thank = True pos : neg = 9.7 : 1.0

fan = True pos : neg = 9.7 : 1.0

lost = True neg : pos = 9.3 : 1.0

Just to see that our model works, let's try the classifier out with a positive example:

example1 = "this workshop is awesome."

print(classifier.classify(format_sentence(example1)))'pos'

Now for a negative example:

example2 = "this workshop is awful."

print(classifier.classify(format_sentence(example2)))'neg'

Now, there's no point in building a model if it doesn't work well. Luckily, once again, nltk comes to the rescue with a built in feature that allows us find the accuracy of our model.

from nltk.classify.util import accuracy

print(accuracy(classifier, test))0.9562326869806094

Turns out it works decently well!

If you have input data x and want to classify the data into labels y. A generative model learns the joint probability distribution p(x,y) and a discriminative model learns the conditional probability distribution p(y|x).

Here's an simple example of this form:

(1,0), (1,0), (2,0), (2, 1)

p(x,y) is

y=0 y=1

-----------

x=1 | 1/2 0

x=2 | 1/4 1/4

Meanwhile,

p(y|x) is

y=0 y=1

-----------

x=1 | 1 0

x=2 | 1/2 1/2

Notice that if you add all 4 probabilities in the first chart, they add up to 1, but if you do the same for the second chart, they add up to 2. This is because the probabilities in chart 2 are read row by row. Hence, 1+0=1 in the first row and 1/2+1/2=1 in the second.

The distribution p(y|x) is the natural distribution for classifying a given example x into a class y, which is why algorithms that model this directly are called discriminative algorithms.

Generative algorithms model p(x, y), which can be tranformed into p(y|x) by applying Bayes rule and then used for classification. However, the distribution p(x, y) can also be used for other purposes. For example you could use p(x,y) to generate likely (x, y) pairs.

==========================================================================================

This guide was written in R 3.2.3.

Then, on your command line, install the needed modules as follows:

pip3 install sklearn

Classification is a machine learning algorithm whose output is within a set of discrete labels. This is in contrast to Regression, which involved a target variable that was on a continuous range of values.

Throughout this tutorial we'll review different classification algorithms, but you'll notice that the workflow is consistent: split the dataset into training and testing datasets, fit the model on the training set, and classify each data point in the testing set.

Discriminant Analysis is a statistical technique used to classify data into groups based on each data point's features.

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) is a linear classification algorithm used for when it can be assumed that the covariance is the same for all classes. Its mostly used as a dimension reduction technique in the pre-processing portion so that the different classes are separable and therefore easier to classify and avoid overfitting.

LDA is similar to Principal Component Analysis (PCA), but LDA also considers the axes that maximize the separation between multiple classes. It works by finding the linear combinations of the original variables that gives the best separation between the groups in the data set.

Quadratic Discriminant Analysis, on the other hand, is used for heterogeneous variance-covariance matrices. Because QDA has more parameters to estimate, it's typically less accurate than LDA.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) is a machine learning algorithm used for classification tasks. Its primary goal is to find an optimal separating hyperplane that separates the data into its classes. This optimal separating hyperplane is the result of the maximization of the margin of the training data.

Let's take a look at the scatterplot of the iris dataset that could easily be used by a SVM:

Just by looking at it, it's fairly obvious how the two classes can be easily separated. The line which separates the two classes is called the separating hyperplane.

In this example, the hyperplane is just two-dimensional, but SVMs can work in any number of dimensions, which is why we refer to it as hyperplane.

Going off the scatter plot above, there are a number of separating hyperplanes. The job of the SVM is find the optimal one.

To accomplish this, we choose the separating hyperplane that maximizes the distance from the datapoints in each category. This is so we have a hyperplane that generalizes well.

Given a hyperplane, we can compute the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data point. With this value, we can double the value to get the margin. Inside the margin, there are no datapoints.

The larger the margin, the greater the distance between the hyperplane and datapoint, which means we need to maximize the margin.

Recall the equation of a hyperplane: wTx = 0. Here, w and x are vectors. If we combine this equation with y = ax + b, we get:

This is because we can rewrite y - ax - b = 0. This then becomes:

wTx = -b Χ (1) + (-a) Χ x + 1 Χ y

This is just another way of writing: wTx = y - ax - b. We use this equation instead of the traditional y = ax + b because it's easier to use when we have more than 2 dimensions.

Let's take a look at an example scatter plot with the hyperlane graphed:

Here, the hyperplane is x2 = -2x1. Let's turn this into the vector equivalent:

Let's calculate the distance between point A and the hyperplane. We begin this process by projecting point A onto the hyperplane.

Point A is a vector from the origin to A. So if we project it onto the normal vector w:

This will get us the projected vector! With the points (3,4) and (2,1) [this came from w = (2,1)], we can compute ||p||. Now, it'll take a few steps before we get there.

We begin by computing ||w||:

||w|| = √(22 + 12) = √5. If we divide the coordinates by the magnitude of ||w||, we can get the direction of w. This makes the vector u = (2/√5, 1/√5).

Now, p is the orthogonal prhoojection of a onto w, so:

Now that we have ||p||, the distance between A and the hyperplane, the margin is defined by:

margin = 2||p|| = 4√5. This is the margin of the hyperplane!

Let's perform the iris classification from earlier with a support vector machine model:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import svm, datasets

iris = datasets.load_iris()

X = iris.data[:, :2]

y = iris.targetNow we can create an instance of SVM and fit the data. For this to happen, we need to declare a regularization parameter, C.

C = 1.0

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=1, gamma=1).fit(X, y)Based off of this classifier, we can create a mesh graph:

x_min, x_max = X[:, 0].min() - 1, X[:, 0].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X[:, 1].min() - 1, X[:, 1].max() + 1

h = (x_max / x_min)/100

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h),

np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

plt.subplot(1, 1, 1)Now we pull the prediction method on our data:

Z = svc.predict(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)Lastly, we visualize this with matplotlib:

plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.Paired, alpha=0.8)

plt.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=y, cmap=plt.cm.Paired)

plt.xlabel('Sepal length')

plt.ylabel('Sepal width')

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.title('SVC with linear kernel')

plt.show()Classes aren't always easily separable. In these cases, we build a decision function that's polynomial instead of linear. This is done using the kernel trick.

If you modify the previous code with the kernel parameter, you'll get different results!

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='rbf', C=1, gamma=1).fit(X, y)Usually, linear kernels are the best choice if you have large number of features (>1000) because it is more likely that the data is linearly separable in high dimensional space. Also, you can RBF but do not forget to cross validate for its parameters as to avoid overfitting.

Tuning parameters value for machine learning algorithms effectively improves the model performance. Let’s look at the list of parameters available with SVM.

Notice our gamma value from earlier at 1. The higher the value of gamma the more our model will try to exact fit the as per training data set, leading to an overfit model.

Let's see our visualizations with gamma values of 10 and 100:

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=1, gamma=10).fit(X, y)

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=1, gamma=100).fit(X, y)Penalty parameter C of the error term. It also controls the trade off between smooth decision boundary and classifying the training points correctly. Let's see the effect when C is increased to 10 and 100:

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=10, gamma=1).fit(X, y)

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=100, gamma=1).fit(X, y)Note that we should always look at the cross validation score to have effective combination of these parameters and avoid over-fitting.

As with any other machine learning model, there are pros and cons. In this section, we'll review the pros and cons of this particular model.

SVMs largest stength is its effectiveness in high dimensional spaces, even when the number of dimensions is greater than the number of samples. Lastly, it uses a subset of training points in the decision function (called support vectors), so it's also memory efficient.

Now, if we have a large dataset, the required time becomes high. SVMs also perform poorly when there's noise in the dataset. Lastly, SVM doesn’t directly provide probability estimates and must be calculated using an expensive five-fold cross-validation.

========================================================================

This guide was written in Python 3.6.

Let's install the modules we'll need for this tutorial. Open up your terminal and enter the following commands to install the needed python modules:

pip3 install time

pip3 install sklearn

As we've covered before, there are two general categories that machine learning falls into. First is supervised learning, which we've covered with regression analysis, decision trees, and support vector machines.

Recall that supervised learning is when your explanatory variables X come with an target variable Y. In contrast, unsupervised learning has no labels, so we a lot of X's with no Y's. In unsupervised learning all we can do is try our best to extract some meaning out of the data's underlying structure and do some checks to make sure that our methods are robust.

One example of an unsupervised learning algorithm is clustering! Clustering is exactly what it sounds like. It's a way of grouping “similar” data points together into clusters or subgroups, while keeping each group as distinct as possible.

In this way data points belonging to different clusters will be quite different from each other, too. This is useful because oftentimes we'll come across datasets which exhibit this kind of grouped structure. Now, you might be thinking how are two points considered similar? That's a fair point and there are two ways in which we determine that: 1. Similarity 2. Cluster centroid. We'll go into detail on what these two things mean in the next section.

Intuitively, it makes sense that similar things should be close to each other, while different things should be farther apart. So to formalize the notion of similarity, we choose a distance metric (see below) that can quantify exactly how "close" two points are to each other. The most commonly used distance metric is the Euclidean distance which we should all be pretty familiar with (think: distance formula from middle school), and that's what we'll be using in our example today. We'll introduce some other distance metrics towards the end.

The cluster centroid is the most representative feature of the entire cluster. We say "feature" instead of "point" because the centroid may not necessarily be an existing point in the cluster. You can find it by averaging the values of all the points belonging to a specific group. But any relevant information about the cluster centroid tells us everything that we need to know about all other points in the same cluster.

The k-means algorithm has a simple objective: given a set of data points, it tries to separate them out into k distinct clusters. It uses the same principle that we mentioned earlier: keep the data points within each cluster as similar as possible. You have to provide the value of k to the algorithm, so you should have a general idea of how many clusters you're expecting to see in your data. This sin't a precise science, but we can utilize visualization techniques to help us choose a proper k.

So let’s begin by doing just that. Remember that clustering is an unsupervised learning method, so we’re never going to have a perfect answer for our final clusters, but we'll do our best to make sure that the results we get are reasonable and replicable.

By replicable, we mean that our results can be arrived at by someone else using a different starting point. By reasonable, we mean that our results have to show some correlation with what we expect to encounter in real life.

The following image is just an example of the visualization we might get. Notice the three colors and the ways in which they could be separated, so we can set k to 3. Right now we’re operating under the assumption that we know how many clusters we want, but we’ll go into more detail about relaxing this assumption and how to choose the best possible k at the end of the workshop.

First we initialize three random cluster centroids. We initialize these clusters randomly because every iteration of k-means will "correct" them towards the right clusters. Since we are heading to a correct answer anyway, we don't really care about where we start.

As we explained before, these centroids are our “representative points” -- they contain all the information that we need about other points in the same cluster. It makes sense to think about these centroids as being the physical center of each cluster, so let’s pretend like our randomly initialized cluster centers are the actual centroids, and group our points accordingly. Here we use our distance metric of choice, in this case the Euclidean distance. So for every single data point we have, we compute the two distances: one from the first cluster centroid, and the other from the second centroid. We assign this data point to the cluster at which the distance to the centroid is the smallest. This makes sense, because intuitively we’re grouping points which are closer together.

Now we have something that’s starting to resemble three distinct clusters! But remember that we need to update the centroids that we started with -- we’ve just added in a bunch of new data points to each cluster, so we need our “representative point,” or our centroid, to reflect that.

So we’ll just do quick averaging of all the values within each cluster and call that our new centroid. The new centroids are further "within" the data than the older centroids. Notice that we’re not quite done yet -- we have some straggling points which don’t really seem to belong in either cluster. Let’s run another iteration of k-means and see if that separates out the clusters better. So recall that we’re just computing the distances from the centroids for each data point, and re-assigning those that are closer to centroids of the other cluster.

We keep computing the centroids for every iteration using the steps before. After doing the few iterations, maybe you’ll notice that the clusters don’t change after a certain point. This actually turns out to be a good criterion for stopping the cluster iterations! At that point we’re just wasting time and computational resources. So let’s formalize this idea of a “stopping criterion.” We define a small value, ε, and we can terminate the algorithm when the change in cluster centroids is less than epsilon. This way, epsilon serves as a measure of how much error we can tolerate.

Now we'll move onto a k-means example with images!

Images often have a few dominant colors -- for example, the bulk of the image is often made up of the foreground color and the background color. In this example, we'll write some code that uses scikit-learn's k-means clustering implementation to find the what these dominant colors may be.

Once we know what the most important colors are in an image, we can compress (or "quantize") the image by re-expressing the image using only the set of k colors that we get from the algorithm. We'll be analyzing the two following images:

We'll be using the following modules, so make sure to import them:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.image as mpimg

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from time import timeThen we begin this exercise by reading in the image as a matrix and normalizing it:

img = mpimg.imread("./leo.png")

img = img * 1.0 / img.max()An image is represented here as a three-dimensional array of floating-point numbers, which can take values from 0 to 1. If we look at img.shape, we'll find that the first two dimensions are x and y, and then the last dimension is the color channel. There are three color channels (one each for red, green, and blue). A set of three channel values at a single (x, y)-coordinate is referred to as a "pixel".

width, height, num_channels = img.shape

num_pixels = width * heightWe're going to use a small random sample of 10% of the image to find our clusters:

num_sample_pixels = num_pixels / 10Next we need to reshape the image data into a single long array of pixels (instead of a two-dimensional array of pixels) in order to take our sample.

img_reshaped = np.reshape(img, (num_pixels, num_channels))

img_sample = shuffle(img_reshaped, random_state=0)Now that we have our data, let's construct our k-means object and feed it some data. It will find the best k clusters, as determined by a distance function. We're going to try to find the 20 colors which best represent the colors in the picture, so we set k to 20:

K = 20Here, we're instantiating the kmeans object just as we have done with other machine learning models. the t0 is initialized to track how fast this algorithm takes to fit, which is the next step in this process. Lastly, we just print how long it took. Note: this code has to be run at the same time so we can get an accurate estimate of how long it took!

t0 = time()

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=K, random_state=0)

kmeans.fit(img_sample)

print("K-means clustering complete. Elapsed time: {} seconds".format(time() - t0))The centers of each of the clusters represents a color that was significant in the image. We can grab the values of these colors from kmeans.cluster_centers_. We can also call kmeans.predict() to match each pixel in the image to the closest color, which will let us know the size of each cluster (and also serve as a way to quantize the image)

kmeans.cluster_centers_As you can see, there are K cluster centers, each of which is a RGB color

array([[ 0.59594023, 0.37377197, 0.23699242],

[ 0.07824585, 0.06161205, 0.04534107],

[ 0.98117697, 0.98098147, 0.97990966],

[ 0.29123059, 0.28127983, 0.22996978],

[ 0.88017613, 0.67859817, 0.51104909],

[ 0.52016801, 0.51832098, 0.43664253],

[ 0.37142357, 0.3536061 , 0.2840144 ],

[ 0.27072299, 0.13391563, 0.05868939],

[ 0.97850031, 0.85233569, 0.70350802],

[ 0.47486466, 0.27632579, 0.16393569],

[ 0.67109919, 0.48759544, 0.33595228],

[ 0.01431993, 0.01277512, 0.01052323],

[ 0.47390169, 0.43343523, 0.33971789],

[ 0.21901846, 0.21610278, 0.17843075],

[ 0.57573938, 0.59766436, 0.536443 ],

[ 0.17545493, 0.07990164, 0.03137593],

[ 0.3704485 , 0.19818981, 0.1059725 ],

[ 0.15592512, 0.15792704, 0.13496453],

[ 0.93447602, 0.77906561, 0.61215806],

[ 0.78221744, 0.57008743, 0.40647745]], dtype=float32)

Now, we can predict on sample pixels and see how long that takes:

t0 = time()

labels = kmeans.predict(img_reshaped)

print("k-means labeling complete. Elapsed time: {} seconds".format(time() - t0))You should get an answer under a second! Next, we can construct a histogram of the points in each cluster:

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(labels, bins=range(K+1))

for p, color in zip(patches, kmeans.cluster_centers_):

plt.setp(p, 'facecolor', color)As you might be able to tell from the above histogram, the most dominant color in the scene is the background color, followed by a large drop down to the foreground colors. This isn't all that surprising, since visually we can see that the space is mostly filled with the background color -- that's why it's called the "background".

Now, let's redraw the scene using only the cluster centers. This can be used for image compression, since we only need to store the index into the list of cluster centers and the colors corresponding to each center, rather than the colors corresponding to each pixel in the image.

quantized_img = np.zeros(img.shape)

for i in range(width):

for j in range(height):

# We need to do some math here to get the correct

# index position in the labels array

index = i * height + j

quantized_img[i][j] = kmeans.cluster_centers_[labels[index]]

quantized_imgplot = plt.imshow(quantized_img)

Notice that the image looks similar, but that the gradients are no longer as smooth and there are a few image artifacts scattered throughout. This is because we're only using the k best colors, which excludes the steps along the gradient.

In our very first example, we started with k = 3 centroids. In case you're wondering how we arrived at this magic number and why, read on.

Sometimes, you may be in a situation where the number of clusters is provided to you beforehand. For example, you may be asked to categorize a vast range of different bodily actions to the three main subdivisions of the brain (cerebrum, cerebellum and medulla).

Here you know that you are looking for three main clusters where each cluster will represent the part of the brain the data point is grouped to. So in this situation, you expect to have three centroids.

However, there may be other situations while training in which you may not even know how many centroids to pick up from your data. Two extreme situations generally happen.

You could either end up making each point its own representative (a perfect centroid) at the risk of losing any grouping tendencies. This is usually called the overfitting problem. While each point perfectly represents itself, it gives you no general information about the data as a whole and will be unable to tell you anything relevant about new data that is coming in.

You could end up choosing only one centroid from all the data (a perfect grouping). Since there is no way to generalize an enormous volume of data to one point alone, this method loses relevant distinguishing features of the data.This is kind of like saying that all the people in the world drink water, so we can cluster them all by this feature. In Machine Learning terminology, this is called the underfitting problem. Underfitting implies that we are generalizing all of our data to a potentially trivial common feature.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to determine the optimal value of k. It’s a hard problem: we have to think about balancing out the number of clusters that makes the most sense for our data, while at the same time making sure that we don’t overfit our model to the exact dataset that we have. There are a few ways that we can address this, and we’ll briefly mention them here.

The most intuitive explanation is the idea of stability. If the clusters we obtain represent a true, underlying pattern in our data, it makes sense that the clusters shouldn’t change very much on separate but similar samples. So if we randomly subsample or split our data into smaller parts and run the clustering algorithm again, the cluster memberships shouldn’t drastically change. If they did, that’d be an indication that our clusters were too finely-tuned to the random noise in our data. Therefore, we can compute “stability scores” for a fixed value of k and observe which value of k gives us the most stable clusters. This idea of perturbation is really important for machine learning in general, and will come up time and time again.

We can also use penalization approaches, where we use different criterion such as AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) or BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) to keep the value of k under control.

==========================================================================================

TThis guide was written in Python 3.6.

Let's install the modules we'll need for this tutorial. Open up your terminal and enter the following commands to install the needed python modules:

pip3 install scipy

pip3 install numpy

Recall in data structures learning about the different types of tree structures - binary, red black, and splay trees. In tree based modeling, we work off these structures for classification prediction.

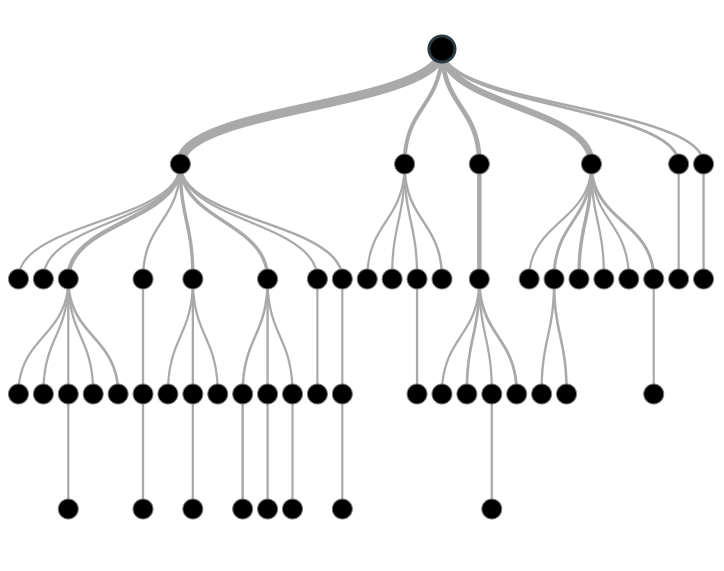

Tree based machine learning is great because it's incredibly accurate and stable, as well as easy to interpret. Despite being a linear model, tree based models map non-linear relationships well. The general structure is as follows:

Decision trees are a type of supervised learning algorithm used in classification that works for both categorical and continuous input/output variables. This typle of model includes structures with nodes which represent tests on attributes and the end nodes (leaves) of each branch represent class labels. Between these nodes are what we call edges, which represent a 'decision' that separates the data from the previous node based on some criteria.

Looks familiar, right?

As mentioned above, nodes are an important part of the structure of Decision Trees. In this section, we'll review different types of nodes.

The root node is the node at the very top. It represents an entire population or sample because it has yet to be divided by any edges.

Decision Nodes are the nodes that occur between the root node and leaves of your decision tree. It's considered a decision node because it's a resulting node of an edge that then splits once again into either more decision nodes, or the leaves.

As mentioned before, leaves are the final nodes at the bottom of the decision tree that represent a class label in classification. They're also called terminal nodes because more nodes do not split off of them.

A node, which is divided into sub-nodes is called parent node of sub-nodes where as sub-nodes are the child of parent node.

-

Easy to Understand: Decision tree output is fairly easy to understand since it doesn't require any statistical knowledge to read and interpret them. Its graphical representation is very intuitive and users can easily relate their hypothesis.

-

Useful in Data exploration: Decision tree is one of the fastest way to identify most significant variables and relation between two or more variables. With the help of decision trees, we can create new variables / features that has better power to predict target variable. You can refer article (Trick to enhance power of regression model) for one such trick. It can also be used in data exploration stage. For example, we are working on a problem where we have information available in hundreds of variables, there decision tree will help to identify most significant variable.

-

Less data cleaning required: It requires less data cleaning compared to some other modeling techniques. It is not influenced by outliers and missing values to a fair degree.

-

Data type is not a constraint: It can handle both numerical and categorical variables.

-

Non Parametric Method: Decision tree is considered to be a non-parametric method. This means that decision trees have no assumptions about the space distribution and the classifier structure.

-

Over fitting: Over fitting is one of the most practical difficulty for decision tree models. This problem gets solved by setting constraints on model parameters and pruning (discussed in detailed below).

-

Not fit for continuous variables: While working with continuous numerical variables, decision tree looses information when it categorizes variables in different categories.

In this output, the rows show result for trees with different numbers of nodes. The column xerror represents the cross-validation error and the CP represents the complexity parameter.

Decision Tree pruning is a technique that reduces the size of decision trees by removing sections (nodes) of the tree that provide little power to classify instances. This is great because it reduces the complexity of the final classifier, which results in increased predictive accuracy by reducing overfitting.

Ultimately, our aim is to reduce the cross-validation error. First, we index with the smallest complexity parameter:

Recall the ensemble learning method from the Optimization lecture. Random Forests are an ensemble learning method for classification and regression. It works by combining individual decision trees through bagging. This allows us to overcome overfitting.

First, we create many decision trees through bagging. Once completed, we inject randomness into the decision trees by allowing the trees to grow to their maximum sizes, leaving them unpruned.

We make sure that each split is based on randomly selected subset of attributes, which reduces the correlation between different trees.

Now we get into the random forest by voting on categories by majority. We begin by splitting the training data into K bootstrap samples by drawing samples from training data with replacement.

Next, we estimate individual trees ti to the samples and have every regression tree predict a value for the unseen data. Lastly, we estimate those predictions with the formula:

where ŷ is the response vector and x = [x1,...,xN]T ∈ X as the input parameters.

Random Forests allow us to learn non-linearity with a simple algorithm and good performance. It's also a fast training algorithm and resistant to overfitting.

What's also phenomenal about Random Forests is that increasing the number of trees decreases the variance without increasing the bias, so the worry of the variance-bias tradeoff isn't as present.

The averaging portion of the algorithm also allows the real structure of the data to reveal. Lastly, the noisy signals of individual trees cancel out.

Unfortunately, random forests have high memory consumption because of the many tree constructions. There's also little performance gain from larger training datasets.

==========================================================================================

TThis guide was written in Python 3.6.

Let's install the modules we'll need for this tutorial. Open up your terminal and enter the following commands to install the needed python modules:

pip3 install scipy

pip3 install numpy

Ensemble Learning allows us to combine predictions from different multiple learning algorithms. This is what we consider to be the "ensemble". By doing this, we can have a result with a better predictive performance compared to a single learner.

It's important to note that one drawback is that there's increased computation time and reduces interpretability.

Bagging is a technique where reuse the same training algorithm several times on different subsets of the training data.

Given a training dataset D of size N, bagging will generate new training sets Di of size M by sampling with replacement from D. Some observations might be repeated in each Di.

If we set M to N, then on average 63.2% of the original dataset D is represented, the rest will be duplicates.

The final step is that we train the classifer C on each Ci separately.

Boosting is an optimization technique that allows us to combine multiple classifiers to improve classification accuracy. In boosting, none of the classifiers just need to be at least slightly better than chance.

Boosting involves training classifiers on a subset of the training data that is most informative given the current classifiers.

The general boosting algorithm first involves fitting a simple model to subsample of the data. Next, we identify misclassified observations (ones that are hard to predict). we focus subsequent learners on these samples to get them right. Lastly, we combine these weak learners to form a more complex but accurate predictor.

Now, instead of resampling, we can reweight misclassified training examples:

Aside from its easy implementation, AdaBoosting is great because it's a simple combination of multiple classifiers. These classifiers can also be different.

On the other hand, AdaBoost is sensitive to misclassified points in the training data.